Table of Contents

Regenerative Rent: Unlocking Urban Value for a Resilient Future

A familiar scene unfolds in cities across the globe. Streets turn to rivers with unprecedented rainfall. Heat waves make asphalt sizzle, forcing residents indoors. Infrastructure, built for a different climate, groans under the strain of a new, harsher reality. These are not merely environmental challenges; they are a profound, existential threat to the financial health of our urban centers. Yet, in this crisis lies a powerful opportunity to re imagine how cities are built and funded. This is the promise of regenerative rent, a bold new paradigm that transforms how we approach urban development, turning public investment into a self-sustaining engine for climate resilience.

The Financial Fault Line: The High Cost of Urban Sprawl

The urban climate crisis is first and foremost a fiscal crisis. The World Economic Forum estimates that climate change damage is costing the world approximately $16 million every hour. This figure, while astounding, is a significant understatement, with the total annual cost of climate damage projected to rise to between $1.7 and $3.1 trillion by 2050.[Read] In Europe, a single brutal summer of extreme weather, including heat, drought, and floods, has already led to at least €43 billion in short-term economic losses.[Read] These mounting costs are a direct result of urban areas being highly concentrated hubs of financial, infrastructural, and human assets that are acutely vulnerable to climate shocks.[Read]

This financial vulnerability is compounded by the traditional model of urban expansion: unchecked sprawl. This sprawling, low-density development is a hidden economic drain, costing the American economy more than $1 trillion annually in greater spending on infrastructure, public service delivery, and transportation. In sprawled communities, infrastructure costs per person can be 10 to 40% higher compared to compact, connected urban centers.[Read] The fiscal model of sprawl is fundamentally unstable, creating a cycle where the cost of maintaining dispersed infrastructure outpaces the tax revenue it generates. This leaves municipalities with a dangerous choice between deferred maintenance and a constant need for tax increases, while leaving no capital for vital climate resilience projects.

Furthermore, sprawl destroys critical natural systems. A single acre of parking lot generates 16 times more runoff than an undeveloped meadow, polluting waterways and increasing water treatment costs. The destruction of trees, which act as natural air conditioners and stormwater managers, represents a loss of services that would cost tens of thousands of dollars to replace per tree.[Read]

This confluence of costs exposes a massive funding gap. The World Bank estimates that building resilient, low-carbon cities in low- and middle-income countries alone will require an investment of between $256 billion and $821 billion per year through 2050.[Read] Yet, globally, only an estimated $68 billion was spent on climate adaptation on average between 2021 and 2022. This chasm between urgent need and available funding is the central challenge that urban leaders face today.

Adding to this dilemma is a deep-seated paradox: the communities most vulnerable to climate shocks are often the urban poor living in informal settlements, yet their economic suffering is often minimally captured by traditional metrics like Gross Value Added, making it harder to secure the funding they desperately need. To break this cycle, a new financial model is required—one that generates revenue not as a burden, but as a byproduct of intelligent, community-centered growth.

Unlocking Regenerative Rent: A Bold Blueprint for Public Good

The concept of regenerative rent draws its elegant simplicity from an unexpected source: the world of regenerative grazing leases. In this agricultural model, a lease is not just a transaction for a farmer to use land; it is a partnership designed to improve the land’s health, biodiversity, and long-term productivity for both the landowner and the wider ecosystem.[Read]

Over time, these agreements can lead to a demonstrable increase in soil health and crop yields, benefiting everyone involved.[Read] In a similar vein, urban regenerative rent represents a new social contract—a collaboration between the public and private sectors to steward urban land for the benefit of the entire community. It shifts the focus from a purely transactional relationship to a partnership with a shared vision for long-term health and resilience.

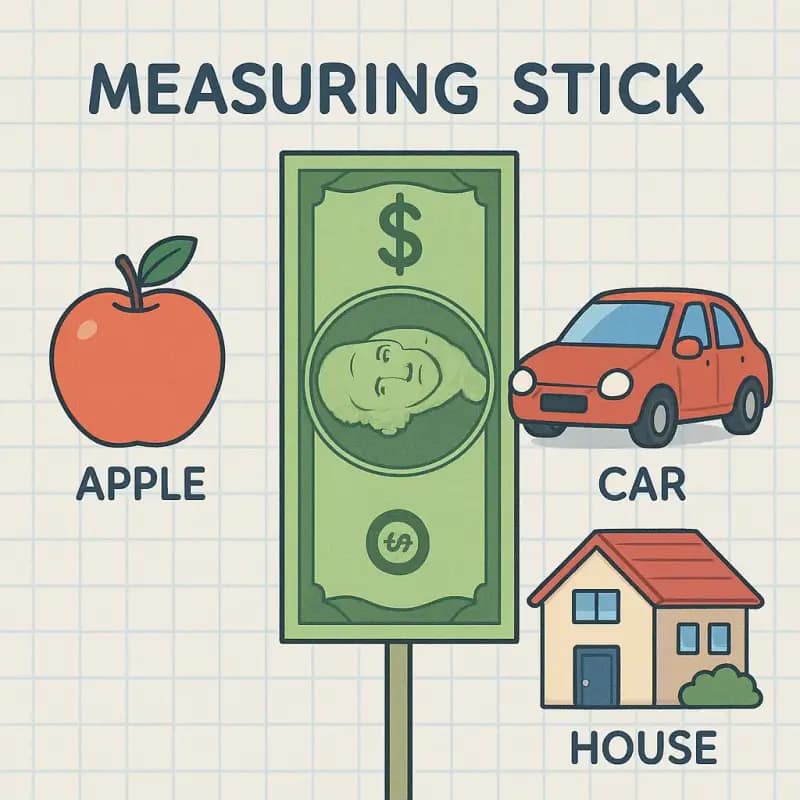

At its core, this idea is a modern application of a centuries-old economic principle. As far back as the 19th century, the American writer Henry George argued that land value is not created by the individual who owns it but by the collective growth of the community itself.[Read] This “unearned increment”—the increase in land value that comes from public investments, such as new transit lines, parks, or rezoning initiatives—is a direct result of public action.[Read] Land value capture (LVC) is the mechanism to mobilize a portion of this value for the benefit of the community at large. The notion is both simple and profound: public action should generate public benefit.[Read]

This is the principle that fuels the “virtuous circle” of regenerative rent. A city invests in public improvements, such as a new waterfront park or a revitalized transit hub.[Read] This public action enhances the desirability of the surrounding area, causing the value of nearby private land to increase. The city then uses a variety of tools to capture a portion of this publicly-created value, which can be reinvested into even more public improvements and resilience measures. This self-financing loop liberates cities from a sole reliance on traditional taxes or strained public budgets, creating a sustainable, long-term funding source.

The reframing of this concept from the technical term “land value capture” to the more holistic “regenerative rent” is a significant shift in philosophy. The word “capture” can imply an act of taking, which has historically contributed to political opposition and implementation failures. In contrast, “regenerative” implies a process of healing and restoration, an active effort to create “net-positive” outcomes for urban ecosystems and human well-being.[Read] This language connects the financial mechanism to a broader, more appealing vision of a city that gives back more than it takes, creating a more harmonious relationship between people and nature.[Read]

From Concrete to Carbon Sinks: How Regenerative Rent Funds Green Infrastructure

The true power of this model is its ability to fund the types of projects that are most essential for climate resilience: nature-based, restorative solutions. The “sponge city” concept, for example, is an urban planning model that uses green infrastructure—such as green roofs, parks, and permeable pavement—to absorb, filter, and store stormwater where it falls.[Read] This elegant approach, a stark departure from the traditional reliance on concrete drainage systems, helps prevent devastating floods while simultaneously improving air quality, enhancing biodiversity, and providing vital public spaces for recreation.

To fund such projects, cities can deploy a diverse toolkit of land value capture instruments. These are not a single, one-size-fits-all solution but a customizable set of policies that can be tailored to a city’s specific legal, economic, and political context.

Case Studies in Action: A Global View

Ahmedabad, India: The Virtuous Riverfront. The city of Ahmedabad offers a quintessential example of how LVC can finance urban regeneration and climate resilience. The city transformed a blighted urban riverfront into a well-serviced, walkable waterfront that dramatically reduced the risk of flooding. A public investment of $17 million was used to construct a 22-kilometer promenade and reclaim land. Through the sale of just 15% of the reclaimed land, the city recouped the entire public investment, creating a self-financing loop for a project that unlocked new development opportunities and provided a critical defense against rising waters.

São Paulo, Brazil: Market-Driven Regeneration. In São Paulo, the city has pioneered a groundbreaking market-based LVC tool called “Certificates of Additional Construction Potential,” or CEPACs.[Read] Developers can purchase these tradable securities at public auction to gain the right to build at a higher density or change the use of a plot.[Read] Since 2004, this innovative approach has generated billions of dollars to fund infrastructure and urban improvements without creating public debt or relying on strained municipal budgets. The revenues are captured in a separate fund dedicated to the specific neighborhood, ensuring the value created is reinvested directly where it is most needed.

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Equity Through Zoning. Land value capture can also be a powerful tool for social equity. The city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, has used Inclusionary Zoning since 1998 to capture value for the direct benefit of its residents.[Read] Under this model, in exchange for the right to build market-rate residential or commercial properties at higher densities, developers are required to provide a certain amount of low- or moderate-income housing. This policy has resulted in the creation of over 1,000 units of affordable rental and ownership housing, demonstrating that LVC can be a mechanism for ensuring equitable growth.

This new era of funding offers a stark contrast to traditional financing models. Instead of relying on limited general funds or international aid that often falls short of the need, these tools create dedicated, self-financing streams of revenue. This shift enables cities to invest proactively in climate resilience and public goods rather than reacting to disasters with a patchwork of insufficient funding.

| LVC Tool | How It Works | Jurisdiction Example | Purpose/Benefit |

| Betterment Levy | A special tax on properties that directly benefit from a public improvement | Manizales,Colombia | Contributed to revenue for urban infrastructure and public improvements |

| Charges for Building Rights (CEPACs) | Developers pay for additional density and building rights in a specific area | São Paulo, Brazil | Generated billions to fund infrastructure and urban renewal without public debt |

| Inclusionary Zoning | Developers provide low- or moderate-income housing in exchange for market-rate development rights | Cambridge, MA | Created thousands of affordable housing units for social equity |

| Land Readjustment | Landowners pool their plots to collectively fund infrastructure and receive a more valuable, improved parcel in return | Japan (Greater Tokyo Railway) | Funded railway expansion and large-scale redevelopment projects |

| Disposition of Public Land | Publicly owned land, enhanced by public infrastructure, is sold or leased to recoup investment | Ahmedabad, India | Recouped the entire upfront cost of a riverfront development project |

The Path Forward: Navigating a More Equitable Future

No urban policy is without its challenges, and regenerative rent is no exception. History offers cautionary tales, such as the United Kingdom’s numerous unsuccessful attempts at implementing land value capture in the 20th century. These failures were often a result of political opposition, a lack of public consensus, and the technical limitations of the time, such as the inability to accurately value land separate from its improvements. The path forward requires a clear-eyed understanding of these hurdles, which can now be overcome with modern data and technology.

The most significant contemporary critique is the paradox of how LVC, intended to create public good, can inadvertently fuel gentrification and housing unaffordability. Critics argue that tools like density bonusing and upzoning increase property values and prices, which puts upward pressure on rents and can displace long-term residents.[Read] The creation of new parks and amenities, while beneficial, can also make a neighborhood more desirable for outsiders, driving up costs for those who already live there.

However, this critique is not a condemnation of the tool itself, but rather a warning about its implementation. A true land value tax, for example, can have the opposite effect. By taxing the value of the land itself, rather than the buildings on it, it disincentivizes speculative land hoarding and encourages developers to build. This is precisely what happened in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where a land value tax was credited with reducing the number of vacant downtown structures from over 4,000 to fewer than 500.[Read] A tax system that does not punish improvements is a powerful force for a denser, more productive, and ultimately more affordable urban landscape.

Ultimately, the problem is not the principle of capturing publicly created value, but the governance and equity framework within which it operates. Opaque, case-by-case negotiations, described by some as “let’s make a deal planning,” often lead to inequitable outcomes and undermine public trust. The solution is a deliberate focus on transparency, community engagement, and a move toward formula-based approaches that ensure the benefits are distributed fairly and justly.

The goal of regenerative rent is not simply to “capture” value but to transition from an extractive mindset to a philosophy of stewardship. This requires that the funds generated are not merely used to finance a road, but to actively restore ecosystems, enhance biodiversity, and build the social cohesion that will make our cities truly resilient.

Frequently Asked Questions About Regenerative Rent

Q. What is the difference between regenerative rent and traditional taxes?

Ans: Regenerative rent is a value-based funding model where the revenue generated is directly tied to the value created by public actions, such as a new park or transit line. In contrast, traditional taxes like income or property tax are not directly linked to a specific public investment or a corresponding increase in private land value.

Q. How can regenerative rent prevent gentrification?

Ans: While some land value capture tools, if poorly implemented, can inadvertently fuel gentrification by raising property values, a true land value tax can combat it. By taxing the value of the land itself—not the buildings on it—this approach discourages land speculation and holding vacant lots, incentivizing developers to build denser, more productive housing that can increase supply and lower prices.

Q. What are the main obstacles to implementing regenerative rent?

Ans: The primary obstacles include a lack of political consensus and public opposition, often due to historical failures and a misunderstanding of the concept. Technical hurdles, such as the need for accurate and transparent land valuation systems, also present a challenge, particularly in developing economies.

Q. Is this a realistic solution for all cities?

Ans: Yes, cities worldwide have already successfully implemented different forms of this concept, from São Paulo’s market-based approach to Cambridge, MA’s focus on affordable housing. The specific tools and their application must be carefully tailored to the local legal frameworks, land market conditions, and unique social needs of each municipality.

How can a city start to implement regenerative rent policies

A city can begin by focusing on a specific project or neighborhood. Piloting a land readjustment scheme or a special assessment for a single, high-impact public improvement can build public trust and test the model’s effectiveness before scaling up. Community engagement from the earliest stages is crucial to building a shared vision.

Our cities stand at a critical juncture. The old models of urban development and finance are proving insufficient to meet the challenges of a warming planet and a growing population. We can no longer afford to build in ways that create fiscal instability and environmental damage. The fiscal fault lines of our cities are widening just as the climate crisis intensifies.

The idea of regenerative rent offers a more elegant and powerful path forward. It is a new social contract that recognizes the land’s value is created collectively and should be stewarded for the collective good. It is a bold blueprint for urban areas to heal themselves, turning public investment into a self-sustaining force for resilience. This is a call to action for urban leaders, developers, and engaged citizens everywhere. We must embrace this idea not merely as a financial mechanism, but as a moral imperative—a chance to build a shared, resilient, and more beautiful urban future.

Engage with our curated reflections on Money, Design, and Society—crafted for discerning minds. Share your perspective, and become part of a dialogue that shapes tomorrow’s world.

.